Fall from the bridge was life-changing

Reg Excell, of Cowes, came to be working on the construction of the Phillip Island bridge in 1968 through a quirk of fate. A shearer by profession, Reg worked in sheds across Australia with the Grazco Company, and at year’s end over the holiday...

Reg Excell, of Cowes, came to be working on the construction of the Phillip Island bridge in 1968 through a quirk of fate.

A shearer by profession, Reg worked in sheds across Australia with the Grazco Company, and at year’s end over the holiday season on Phillip Island, he would knock off for the holiday season and work on Phillip Island as a chef in local guesthouses.

That had been the pattern of his life for the previous six years, during which time he had married wife Helen and had two young children.

However, in 1968, a shearer’s strike was called.

With no job to go back to, Reg applied for work with John Holland, the contractor working on construction of the new bridge between San Remo and Newhaven.

His life was to change forever, however, when he slipped and fell from pier seven six months into the job.

The bridge was already underway when Reg began his new job.

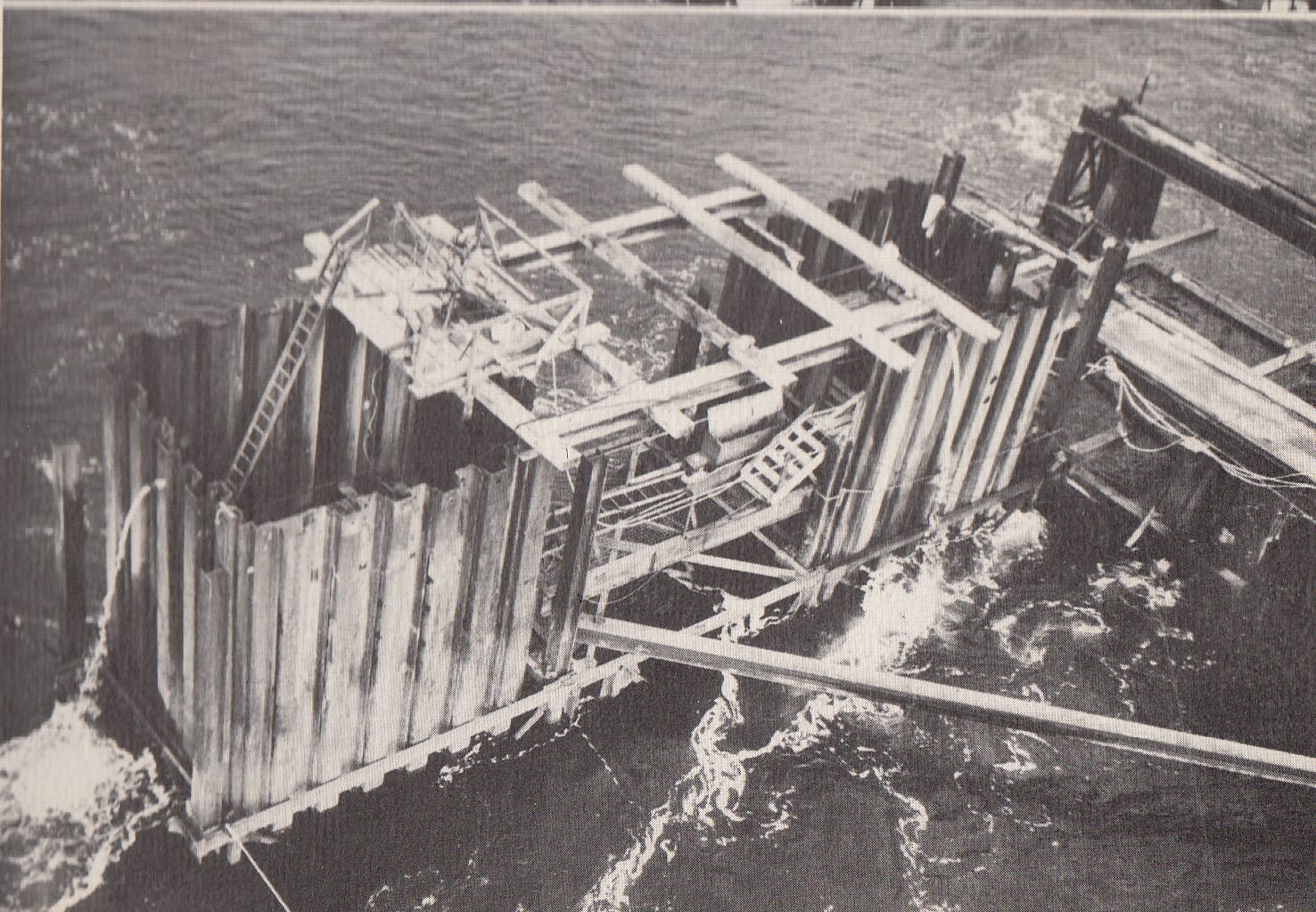

He worked in what were called coffer dams.

These comprised a square steel sided space, which protected an inside cylinder which had an outside diameter of 9 feet and a wall 1 foot 3 inches thick.

This gave two men an inside diameter of seven feet in which to work in.

One jack hammered away at the dirt on the sea floor, while the other dug the loosened material out.

As the dirt was removed, the weight of the cylinder would drop it down a couple of inches at a time.

Occasionally, sea water would swamp the protective coffer dam structure, and the men would have to vacate in a hurry.

The digging and jack hammering proceeded until the cylinder had finally reached the desired depth of 40 to 45 feet below the sea floor.

The men were paid a bonus on top of their salary, according to how far and how fast the cylinder would drop.

The cylinder hole was then pumped with concrete; and this became the base of a bridge pier.

On the fateful day that Reg fell, a concrete pour was taking place.

He slipped in the wet on a steel girder, and fell 25 feet down into the cylinder hole.

It could have been worse. His fall was broken by a steel girder, preventing him dropping another 20 feet.

“There were no safety procedures in those days,” he comments.

He recalls that there were boats stationed under the bridge as a matter of course to haul out anyone who fell in; “and they did” but Reg fell into the cylinder hole.

Unconscious, his workmates wrapped him in a straitjacket, and he was attached to a crane line and hoisted out.

He came to spinning like a top in the air as the crane manoeuvred him back on to the ground.

He suffered compressed fractures of four vertebrae, and a badly injured leg.

There was no ambulance available, so Reg was taken to Wonthaggi hospital in the back of a station wagon.

He was in and out of hospital and rehabilitation centres over the next five years, undergoing back operations and finally having seven vertebrae fused.

It was thought for a while that he would not walk again.

There was no such thing as worker’s compensation in those days.

His fellow workers took up a collection for him.

Sadly, a number of those workers would be killed themselves in the collapse of the West Gate bridge just two years later, in 1970.

Reg still thinks about that.

It was many years before Reg was able to work properly again, and he recalls the kindness of local people toward his family in the intervening period.

“We could not have survived without the financial support of Helen’s parents,” he comments.

Cowes post master Frank Spencer gave him a sedentary job sorting the mail; Reg and Betty Orr at the Hollydene employed him as a chef; State Bank Manager Ray Christiansen waived house repayments for years until the family got back on its feet; and Warley Hospital where Reg spent many months did the same thing.

Reg received a compensation payment after suing John Holland many years later, and this amount was used to cover those debts.

His abiding memory of what was an extremely difficult period is of the help and kindness shown him by the local community.